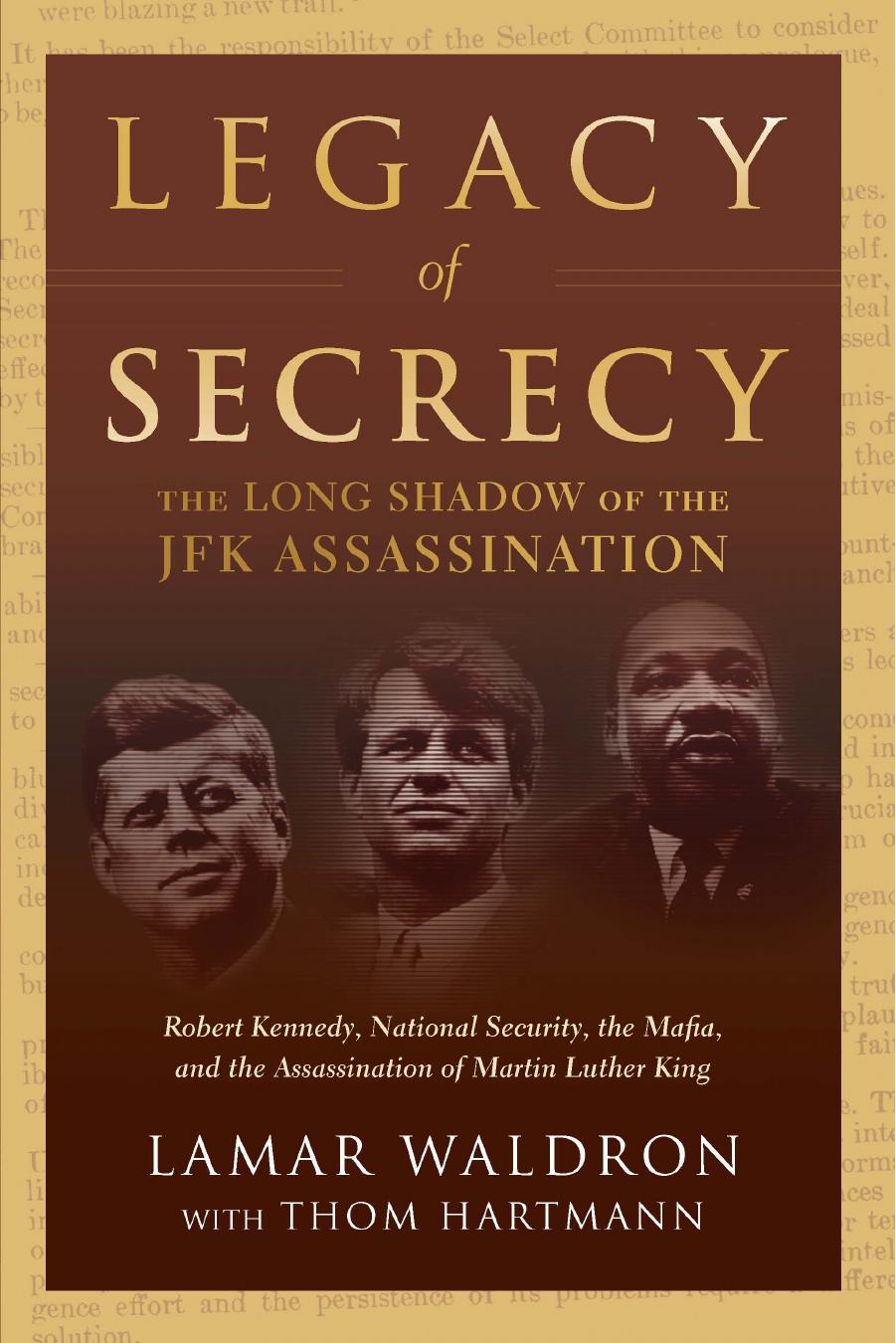

Legacy of Secrecy by Lamar Waldron

Author:Lamar Waldron

Language: eng

Format: epub, pdf

Chapter Thirty-six

453

All of this information had a three-part implication for CIA Cuban

operations in 1967. First, the CIA was trying to downgrade its violent

operatives to a less official status, while still using them. Second, CIA

records, as in the case of Posada’s service dates, were sometimes fudged or

altered when the operative was linked to terrorism or political scandals—

in Posada’s case, that included his involvement in the bombing of a

Cubana airliner, work for the CIA in Iran-Contra, and later attempts to

assassinate Fidel Castro. Finally, drugs were an increasing aspect of anti-

Castro operations in the late 1960s and early ’70s, and the CIA did not

regard drug trafficking (and contact with the Mafia) as a reason to ter-

minate certain operatives. As the CIA had written about Manuel Artime

and AMWORLD in 1964, perhaps the impression that covertly backed

CIA exiles got their weapons and explosives from Mafiosi benefited the

CIA more than the impression that the agency had provided them.22

The bottom line is that the CIA’s method of operation made it increas-

ingly difficult to determine which exiles were actually working for the

CIA—and where their allegiance ultimately lay. That situation had been

a problem while JFK was still alive, and it continued even as CIA super-

vision of exile operatives decreased. The soft treatment of some arrested

exiles might indicate which Cuban exiles were supported or sanctioned

by the CIA. Felipe Rivero’s two men who had been arrested for firing

a bazooka at the UN in 1964 were also questioned in the 1967 Montreal

bombings and “arrested [in the Montreal case] by Jersey City PD for pos-

session of explosives,” according to a June 29, 1967, FBI report. However,

both were released on only a small bond by July 10, 1967.23

In the summer of 1967, Felipe Rivero’s men formed an alliance with

another group, headed by Cuban exile Juan Bosch. A July 14, 1967, FBI

report says that one of Bosch’s men negotiated with a “Cuban exile

arms dealer in Miami . . . to order .30 and .50 caliber machine guns, a 20

millimeter cannon, a 57 millimeter recoilless rifle, and a large amount

of ammunition for these weapons.” That arrangement might have been

related to an incident two days later, in which author Jane Franklin

writes that Cuban authorities captured several exiles in a speedboat

who were “armed with high-powered rifles, cyanide bullets, and a plot

to assassinate [Fidel].” On July 19, 1967, an FBI memo said that Juan

Bosch and five of his men “were indicted in Miami . . . and charged with

conspiracy to export arms.” However, they were freed on $1,000 “recog-

nizance bonds.” Five days later, the FBI says, Bosch and some of his men

were “indicted at Macon, [Georgia] . . . for attempting to export arms,”

yet they were freed once more on only “recognizance bonds.”24

454

LEGACY OF SECRECY

The soft treatment of Bosch, his men, and Rivero’s associates by

US authorities raise suspicion that their activities were approved at

least tacitly by someone in the CIA. The same idea applies to Felipe

Rivero, whom the FBI described on July 11, 1967, as “excludable and

deportable”—yet he was never deported. Likely not approved by

the CIA, however, were the

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19097)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12194)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8915)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6891)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6283)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5805)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5763)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5511)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5452)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5221)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5155)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5089)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4965)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4929)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4793)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4755)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4721)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4516)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4492)